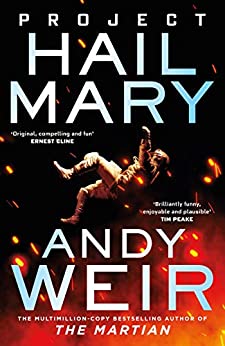

Much like Andy Weir’s bestselling debut, The Martian, Project Hail Mary’s central premise doesn’t stray too far from the requirements for a film treatment. It feels just a little old-fashioned, yet almost machine tooled for a GCI-heavy Hollywood adaptation.

Project Hail Mary follows a classic three-act structure and features a flawed, decent hero with a determinedly PG-13 inner life. My personal fantasy casting agent seeks John Krasinski for the role, channelling a little each of Harrison Ford, Carl Sagan, Paul Stamets and Ned Flanders, if anyone were curious.

Project Hail Mary begins with said hero waking from a coma, light-years from home, with significant gaps in his memory.

From this tried-and-true opening gambit, Weir executes his narrative burlesque with precision: teasing glimpses of the all-important ‘why’ and ‘how’ interleaved with moments of bleak humour, silliness and heart-in-throat jeopardy. With each reveal, we learn the exact circumstances that make Ryland Grace, a middle-grade teacher who loves ‘his’ kids, humanity’s last hope for reversing an apocalyptic climate event.

Per conventions of the deathless Hollywood sub genre of White People In Space (see Interstellar, First Man, Gravity) there is, of course, more to Grace’s cool-teacher schtick, his ordinariness and professional stagnation than meets the eye. It also emerges amnesia isn’t the sole reason for Grace’s unreliability as narrator of his own story.

Hail Mary’s aims, petty stumbling blocks and failures are entirely human and earthbound, as are Grace’s, though Weir makes the hopeful assertion that the solutions to such an immense problem are human, too.

Grounded in the actual and the just-about-possible, Project Hail Mary satisfies with detail of solving the seemingly unsolvable. Grace’s struggles and victories are replete with nerdy joys – we see just how to save the world with pluck, creaky jokes, coffee and science!

Conveyed with equal, unabashed glee and wonder are first contact with extraterrestrial life and delving into the culture, language and taboos of another world. Weir’s imagined parallel evolution of intelligent life in another solar system contains enough complexity to convince without being weighted down by his commitment to research.

Project Hail Mary suffers at times from a less enlightened, curious perspective on the massive international effort behind its titular work. Despite a push to make things happen for the good of mankind from expert teams everywhere, Project Hail Mary heavily implies saving the world’s still a job for an American (White, Straight) Male, a viewpoint which still harms and informs the Western world’s cultural landscape.

Weir’s broad characterisations of his peripheral players lead to occasional wince-worthy cliches. Hard-drinking Russians and socially inept physicists, while irksome, don’t detract from a story that’s tense in the way of a solid adventure (as opposed to the hell-is-other-people way), absorbing and affirming, at a collective moment in which the end of life as we know it feels too close at hand.

Project Hail Mary deviates from the tried-and-true formula in one essential respect: it is, best of all, enormous fun.

Review by M.M. Hattab